Your fear is your superpower

Lessons from the operating room on anxiety, fear, and falling in love with failure

My hands look steady. They place each suture where it’s supposed to go. They thankfully don’t betray me when the scrub nurse puts scissors in them.

Inside, my chest is crushed in a vice. My breathing is shallow. And my brain roils worse than a ship in the Bay of Biscay.

“What if you can’t do this?” my brain asks me, the patient’s face literally wide open in front of me. “You know what, never mind. You know you can’t do this. Your repair is just going to break down, your reconstruction is bound to fail, and then what? You’re screwed. He’s screwed.

“You shouldn’t be here.”

I know that voice. I know this feeling. I’ve written a lot about the fact that I live with anxiety, my jagged traveling companion. And this—the racing heart, the shallow breathing, the catastrophic thinking? He’s back.

And worse. He’s got a point.

Let’s back up.

A few years ago, I met Sebastian (not his real name). He had a tumor on his jaw that I had taken out. I’d replaced the diseased mandible with a metal plate, rotated some muscle over it, and closed everything up. I’ve done this operation hundreds and hundreds of times. And Sebastian looked great, just like his predecessors.

He looked great, that is, until he didn’t. Two weeks after the original operation, Sebastian’s face broke down.

Every single incision pulled apart, leaving gaps wide enough that you could see his tongue through his neck. His spit bathed his chest.

It was, to use the technical word for it, real bad.

It’s hard to describe the sinking feeling you get as a surgeon when one of your wounds opens up. We all know that complications happen—the only surgeon who doesn’t face complications is the one who doesn’t operate—but still. Even a small dehiscence can make you question your competence, to say nothing of a total and complete wound breakdown like Sebastian had.

It was obvious I’d have to take Sebastian back to the operating room, obvious that I was going to have to find a new way to reconstruct the hole in his neck.

Except. I operate on a hospital ship in Africa. And although that ship is extremely well stocked and although its perioperative care is second-to-none, the fact remains that we can’t provide the same types of surgeries you’d see in an academic center in the US. Reconstructive options we’d turn to at home—moving his fibula to his jaw, for example—were not available to me.

And that’s how, two weeks after his first operation, I’m back in the OR, attempting a second reconstruction, with one terrifying thought on repeat: if this next reconstruction fails, I’m out of options.

It’s those last four words—I’m out of options—that I want to drill down on today.

Because they’re the sneaky part of anxiety, the part that we don’t focus on enough.

We talk about the panic, the rapid and shallow breathing, the chest tightening. We talk about “tricks” to “make anxiety go away” (the next time someone tells me I just need to count five things I can see, four things I can hear, and three things I can touch…).

But what we don’t talk about nearly enough is the fact that fear makes you feel like you’re out of options.

See, it doesn’t just tell you that the worst possible thing is going to happen, it also convinces you that you don’t have the resources to handle it.

Walking life with my jagged companion is like having an overprotective friend who’s constantly catastrophizing—except that friend also has access to all your insecurities. Not only does he get to catastrophize, he also knows you well enough to tell you all the ways that you—specifically you—are incapable of navigating the impending catastrophe.

The worst is about to happen and you’re out of options. The challenge will be great and you’re not up to the task.

Someone’s face was literally open in front of me on the operating table, and all my traveling companion could do was tell me that, no matter what I did, I was going to fail.

And that feels devastatingly awful.

Chinese finger traps and willingness dials

I’ve learned two things about living with anxiety for the last quarter century.

First, you can’t make it go away. In fact, the harder you struggle, the worse the anxiety gets. Any time I’m trying to count two things I can smell, my brain knows what’s happening. “Oh, you’re trying to make the anxiety go away, are you? How cute! Here’s more of it.”

It’s like those Chinese finger traps: the harder you try to get out, the tighter a grip they have on you.

Source: Etsy

So first, you can’t make it go away.

And second, it always goes away.

I learned this after fifteen years of flight anxiety, one of only two places I’ve had frank panic attacks (the other one was on a public speaking stage).

Back in the 2000s, the panic attacks would start the minute the “Boarding is complete” announcement would come across the PA, and nothing I did would make them go away.

Except letting them come.

Except turning the willingness dial up to 11.

Except allowing the anxiety.

I learned, though, that if I let the anxiety come without fighting it, if I let it do its thing, if I relaxed my grip on the finger trap, the attack would always pass.

(Side note: Everyone’s anxiety is different. If you suffer from anxiety, please, please, please don’t take psychiatric advice for your particular condition from a surgeon!)

The only problem is, when someone’s face is open in front of you, you can’t just take a break to let the anxiety do its thing. You’ve got to accept the anxiety and keep operating.

Easy to say. Incredibly hard to do. Acknowledging without trying to fight is not something I’m good at.

And that’s exactly where anxiety’s superpower lies.

Your anxiety is a superpower

I get it, it’s far too hip these days to call something a superpower. It can also feel really false. If you’ve ever been anxious in your life, you know that anxiety doesn’t feel good. You know that the fear of failure hurts. You know that panic can be crippling.

The last thing you want to hear—and the last thing I want to tell you—is that you need to change that.

You don’t. Anxiety sucks. Panic sucks. Failure hurts.

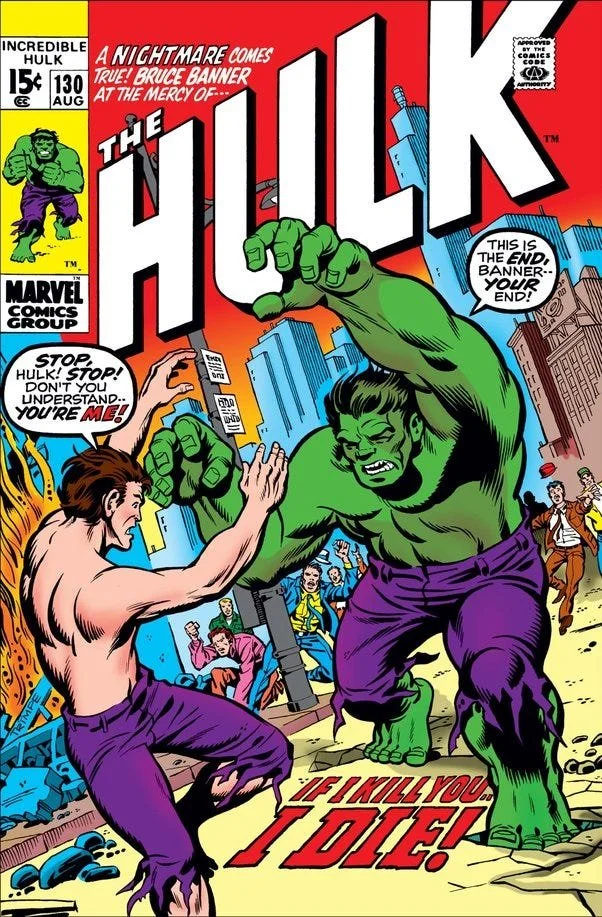

That, however, doesn’t change how much of a superpower it is. After all, The Hulk didn’t like his superpower either.

Anxiety’s superpower is very specific.

Fear points you to your purpose.

The thing you’re anxious about is the very thing you care deeply about. Think about it this way: only the person who cares about social interaction can have social anxiety. Only the person who cares about how they do on an exam can have test anxiety.

Because if they didn’t care, they’d have no reason to be anxious.

Let me say it again:

Your pain points you to your purpose.

In Acceptance and Commitment Therapy, there’s a concept called “The Struggle Switch.” When it’s on, you struggle, you fight against your anxiety.

But when you flip that switch off—by no longer trying to make the anxiety go away, but instead by accepting its presence—something absolutely remarkable happens:

The anxiety doesn’t go anywhere, and at the same time, it loses its power to paralyze you.

Which—finally—allows you to see what it’s pointing you toward.

And that brings me back to Sebastian. See, the anxiety wasn’t just telling me that I couldn’t do it. It was, at the same time, telling me why it mattered, pointing me to what I valued most — my patient’s wellbeing, my commitment to excellence, my desire to help others heal.

So, here’s a radical suggestion: don’t just accept anxiety — fall in love with it. Fall in love with the pain, with the sucky feeling, with the narrowing tunnel vision.

Go beyond just “accepting” fear, to falling deeply in love with its superpower.

Not because failure feels good, Bruce Banner, but because it’s evidence that you’re attempting something worthwhile. Every failed attempt, every setback, every moment of doubt is a signal that you’re pushing beyond your comfort zone, trying to create something meaningful.

Your anxiety, your fear of failure, your moments of doubt — they’re not weaknesses. They’re compass needles pointing toward what matters most to you.

They’re the price of admission for doing work that matters.

Because here’s a hard life truth: the goal isn’t to eliminate anxiety or avoid failure. The goal is to build a life where we can take meaningful action even when—especially when—things get hard.

(Oh, and Sebastian? His second reconstruction worked beautifully. Sometimes the thing you’re most afraid of turns out to be the path to your greatest success.)

Want to learn more about making confident decisions even in the face of uncertainty? Join my mailing list for weekly decision-making content! Bonus: my new guide, “The Anatomy of a Good Decision,” is free for everyone who joins the mailing list before 2024!

It’s a framework I’ve developed to help you approach any decision with clarity and confidence—no matter how complex it might seem.